Chances are, if you’re interested in astronomy, that you’ve heard of William Herschel. A bit of a polymath, he was an accomplished musician, composer and even philosopher, but is best known for his discovery of Uranus, the first planet to be discovered with a telescope (one he’d built himself). Someone you might not be as familiar with, however, is Caroline Herschel – William’s younger sister. She herself was a brilliant astronomer, having been trained as William’s assistant throughout her life.

The two siblings didn’t start in astronomy though. Both William and Caroline Herschel were born in Hanover, twelve years apart (William in 1738, Caroline in 1750) and William, at least, was raised to follow in their father’s footsteps and be a musician. William (or Wilhelm at the time) played many instruments and soon moved to England where he had several prestigious positions before settling in Bath as an Organist for a church.

Caroline, much younger than William, was given a meagre education – she learned to read and write and not much more. Her father was keen to have her educated, but her mother was not – she wanted Caroline to become a house-servant. This was due to Caroline’s health – she had been infected with typhus when she was young, stunting her growth (she remained just over four feet tall throughout her life), as well as leaving her blind in one eye. Due to this her mother thought she would never marry and that it was better if she became the family’s servant. She was mainly overwhelmed with household chores – by the time she was five her only sister had gotten married and moved away, and so Caroline was left solely responsible for the house. She did manage to learn a little needlework from her friends and neighbours, but was prevented from learning French and more detailed needlework, so that she couldn’t become a governess and attain independence. Despite ruling over Caroline’s life in many ways, her mother was actually absent for a lot of Caroline’s adolescence, and so Caroline’s Father often snuck her into her brothers’ violin lessons. His attempts to educate her further were only minorly successful, and ceased when he died.

After their Father’s death, William and his brothers decided that it would be good for Caroline to come and live with William in Bath. When she moved to England, she helped William with his musical pursuits. He had a flourishing musical career, as a teacher, organist and choirmaster, and Caroline, finally out from under the foot of their mother, began to flourish too. She became a well-known and accomplished singer during this time, and gave various public concerts, organised by her brother. William also continued her education – aside from multiple music lessons a day, she learnt arithmetic, English and dancing. The pinnacle of her musical career came when she was asked to be the first soloist in a performance of Handel’s Messiah in the Birmingham festival. Unfortunately this was one of the last big performances of her career as well. The problem was that she wouldn’t sing for any conductor other than her brother, and he had become more occupied by astronomy by this time.

Destined to follow her brother throughout life, Caroline followed him into astronomy as well; although begrudgingly. “I did nothing for my brother but what a well-trained puppy dog would have done” was her thinking – but eventually she did begin to enjoy astronomy.

The first thing William did when he moved into astronomy was learn to make his own telescope lenses, and he taught Caroline this too. He was unsatisfied with the quality of the lenses he was able to buy, and so he ground his own – and they would prove to be better than others of the time when they allowed him to discover Uranus. William was obsessed – Caroline often had to force him to stop and eat.

Caroline, though, was a good astronomer herself by this point. She ground and polished lenses, took astronomical readings (a tricky task) and mounted telescopes to get the best view. The Herschels had moved away from Bath at this point, much to Caroline’s disgust –she had enjoyed the high society they were part of there, and found Datchet awful, but had started her own work in astronomy in earnest. She started by gradually and methodically searching for new objects in the night sky, and even began her own record book. On 26th February 1783, her hard work paid off for the first time. She discovered a nebula. And then another, right on that same night. William, who had been off and occupied by his work for the King, was enthused by this, and relegated Caroline to operating a telescope and doing impossible tasks, that William himself had failed at, while he did the searching for new nebulae. He quite soon discovered, though, that he was fighting a losing battle, and needed an assistant – and came crawling back to Caroline for help.

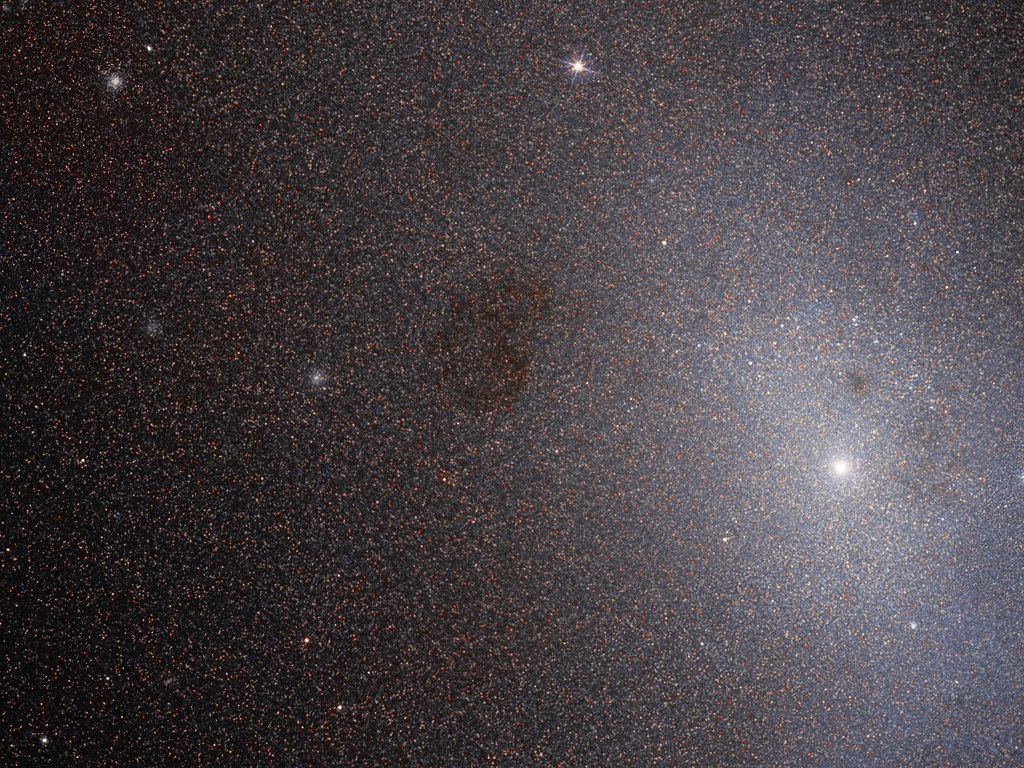

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

WIlliam had seemed to recognise Caroline’s skill by now, and built her her very own Comet searching telescope. She of course had to act as William’s assistant first and foremost, a very skilled job which eventually required her to come up with her own catalogue of nebulae, which she kept and updated with meticulous effort. Despite this, she still managed to discover eight comets by 1797 (including rediscovering Comet Encke) , making her the second woman to have discovered a comet.

During this time, where she had managed to do her own work as well as help her brother, she was asserting independence from William, and this was finally recognised in 1787 when the crown awarded her a salary for her scientific work. She was the first woman to be recognised this way, and was soon known as an excellent astronomer irrespective of William.

William got married during this time – which threw a bit of a spanner in the works for Caroline. She was moved to lodgings outside the main house, and no longer had the keys to the observatory, where she had previously carried out her own work. However, Caroline was fond of her sister-in-law and her nephew, speaking kindly of both. Some think, though, that she was at first jealous and bitter of her brother’s wife, and that it took her a while to warm up to her. It is unclear how she actually felt, as none of her journals from this time period survived.

Throughout this time, though, she carried on her work, producing catalogues of nebulae and even having her work published (albeit under William’s name). She continued creating her catalogue of nebulae, organised by polar distance, a much more useful arrangement for practical astronomy, than existing catalogues. This allowed her nephew, John Herschel, another great astronomer, to carry out his work, reexamining the nebulae William and Caroline had recorded.

When her brother died, Caroline was heartbroken and moved back to Hanover. She attempted to continue with the work of verifying her and her brother’s findings as well, but found Hanover to be unsuitable for astronomy, and instead spent most of her time working on the catalogue, which was eventually (right here in Armagh) expanded, and became the NGC – the New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars.

Throughout her life Caroline was a hard worker and an excellent astronomer, and although in the early days she was overshadowed by her brother, towards the end of her life she was honoured with awards and accolades. The Royal Astronomical Society awarded her with their Gold medal for her work on her catalogue – she was the first woman to be awarded this honour. They also later elected her an honorary member of the society – again she was the first woman to be chosen for this, along with Mary Somerville (A scottish scientist). She was awarded another Gold Medal when she was 96, this time by the King of Prussia, for her work throughout her life.

She died in Hanover, in 1848 at the age of 98 – a long and exciting life, although it may not have seemed so to her at certain points. Since her death, several astronomical objects have been named for her, including an asteroid, two NGC objects and a satellite, not to mention the comets she discovered.

So, while history may remember her brother as a great astronomer, and may sometimes forget Caroline, she absolutely deserves to be recognised as the great astronomer she was – especially in a time when women were overlooked.

1 Comment

gracey · February 22, 2021 at 23:06

Hello, I have a big project about caroline Herschel and I think she is an amazing person.